BATTLE OF OKINAWA

BATTLE OF OKINAWA

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia and others

| Battle of Okinawa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II, the Pacific War | |||||||

A Marine from the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines on Wana Ridge provides covering fire with his Thompson submachine gun, May, 1945 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 183,000[1] | 117,000[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 12,513 killed 38,916 wounded, 33,096 non-combat losses |

About 95,000 killed 7,400–10,755 captured |

||||||

| Estimated 42,000–150,000 civilians killed | |||||||

he Battle of Okinawa, codenamed Operation Iceberg, was fought on theRyukyu Islands of Okinawa and was the largest amphibious assault in the Pacific War. The 82-day-long battle lasted from early April until mid-June, 1945. After a long campaign of island hopping, the Allies were approaching Japan, and planned to use Okinawa, a large island only 340 miles away from mainland Japan, as a base for air operations on the planned invasion of Japanese mainland (coded Operation Downfall). Five divisions of the U.S. Tenth Army, the 7th, 27th, 77th, 81st, and 96th, and two Marine Divisions, the 1st and 6th, fought on the island while the 2nd Marine Divisionremained as an amphibious reserve and was never brought ashore. The invasion was supported by naval, amphibious, and tactical air forces.

The battle has been referred to as the “Typhoon of Steel” in English, and tetsu no ame (“rain of steel”) or tetsu no bōfū (“violent wind of steel”) in Japanese. The nicknames refer to the ferocity of the fighting, the intensity of Kamikaze suicide attacks from the Japanese defenders, and to the sheer numbers of Allied ships and armored vehicles that assaulted the island. The battle resulted in the highest number of casualties in the Pacific Theater during World War II. Japan lost over 100,000 troops killed or captured, and the Allies suffered more than 50,000 casualties of all kinds. Simultaneously, tens of thousands of local civilians were killed, wounded, or committed suicide. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki caused Japan to surrender just weeks after the end of the fighting at Okinawa.

Order of battle

Land

The U.S. land forces involved included the Tenth Army, commanded by Lieutenant General Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr. The army had twocorpsunder its command, III Amphibious Corps under Major General Roy Geiger, consisting of 1st and 6th Marine Divisions, and XXIV Corpsunder Major General John R. Hodge, consisting of the 7thand 96th Infantry Divisions. The 2nd Marine Division was an afloat reserve, and Tenth Army also controlled the 27th, earmarked as a garrison, and 77th Infantry Divisions. In all, the Tenth Armycontained 102,000 Army and 81,000 Marine Corps personnel.

Commanders of the Japanese 32nd Army, February 1945

The Japanese land campaign (mainly defensive) was conducted by the 67,000-strong (77,000 according to some sources) regular Thirty-Second Army and some 9,000 Imperial Japanese Navy(IJN) troops at Oroku naval base (only a few hundred of whom had been trained and equipped for ground combat), supported by 39,000 draftedlocal Ryukyuan people (including 24,000 hastilyconscripted rear militiacalled Boeitai and 15,000 non-uniformed laborers).

Senior officers prepare for Okinawa

In addition, 1,500middle school senior boys organized into front-line-service “Iron and Blood Volunteer Units”, while 600 Himeyuri Studentswere organized into a nursing unit.

The 32nd Army initially consisted of the 9th, 24th, and 62nd Divisions, and the 44th Independent Mixed Brigade. The 9th Division was moved to Taiwan prior to the invasion, resulting in shuffling of Japanese defensive plans. Primary resistance was to be led in the south by Lieutenant GeneralMitsuru Ushijima, his chief of staff, Lieutenant General Isamu Chō and his chief of operations, Colonel Hiromichi Yahara.

Yahara advocated a defensive strategy, whilst Chō advocated an offensive one. In the north, Colonel Takehido Udo was in command. The IJN troops were led by Rear Admiral Minoru Ota. They expected the Americans to land six to ten divisions against the Japanese garrison of two and a half divisions. The staff calculated that superior quality and numbers of weapons gave each U.S. division five or six times the firepower of a Japanese division; to this would be added the Americans’ abundant naval and air firepower.

Underground Hangar. Crops were planted on top rendering it virtually impossible to see from the air. – Ctsy. Wayland Mayo

Sea

U.S. Navy

Most of the air-to-air fighters and the small dive bombers and strike aircraft were U.S. Navy carrier-based airplanes. The Japanese had usedkamikaze tactics since the Battle of Leyte Gulf, but for the first time, they became a major part of the defense. Between the American landing on April 1 and May 25, seven major kamikaze attacks were attempted, involving more than 1,500 planes. The U.S. Navy sustained greater casualties in this operation than in any other battle of the war.

British Commonwealth

Although Allied land forces were entirely composed of U.S. units, the British Pacific Fleet (BPF; known to the U.S. Navy as Task Force 57) provided about a quarter of Allied naval air power (450 planes). It comprised many ships, including 50 warships of which 17 were aircraft carriers, but while the British armoured flight decks meant that fewer planes could be carried in a single aircraft carrier, they were more resistant to kamikaze strikes. Although all the aircraft carriers were provided by the UK, the carrier group was a combined British Commonwealth fleet with British, Canadian, New Zealandand Australian ships and personnel. Their mission was to neutralize Japanese airfields in the Sakishima Islands and provide air cover against Japanese kamikaze attacks.

Bombing Okinawa

KAMIKAZE

The Kamikaze (神風?, common translation: “divine wind”) [kamikaꜜze](![]() listen) Tokubetsu Kougekitai (特別攻撃隊?) Tokkō Tai (特攻隊?) Tokkō (特攻?) were suicide attacks by military aviators from the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, designed to destroy as many warships as possible.

listen) Tokubetsu Kougekitai (特別攻撃隊?) Tokkō Tai (特攻隊?) Tokkō (特攻?) were suicide attacks by military aviators from the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, designed to destroy as many warships as possible.

Kamikaze pilots would attempt to crash their aircraft into enemy ships—planes often laden with explosives,bombs, torpedoes and full fuel tanks. The aircraft’s normal functions (to deliver torpedoes or bombs or shoot down other aircraft) were put aside, and the planes were converted to what were essentially manned missiles in an attempt to reap the benefits of greatly increased accuracy and payload over that of normal bombs. The goal of crippling as many Allied ships as possible, particularly aircraft carriers, was considered critical enough to warrant the combined sacrifice of pilots and aircraft.

These attacks, which began in October 1944, followed several critical military defeats for the Japanese. They had long lost aerial dominance due to outdated aircraft and the loss of experienced pilots. On a macroeconomic scale, Japan experienced a decreasing capacity to wage war, and a rapidly decliningindustrial capacity relative to the United States. The Japanese government expressed its reluctance to surrender. In combination, these factors led to the use of kamikazetactics as Allied forces advanced towards the Japanese home islands.

While the term “kamikaze” usually refers to the aerial strikes, the term has sometimes been applied to various other intentional suicide attacks. The Japanese military also used or made plans for Japanese Special Attack Units, including those involving submarines, human torpedoes, speedboats anddivers.

Although kamikaze was the most common and best-known form of Japanese suicide attack during World War II, they were similar to the “banzai charge” used by Japanese infantrymen (foot soldiers). The main difference between kamikaze and banzai is that death was inherent to the success of a kamikaze attack, whereas a banzai charge was only potentially fatal — that is, the infantrymen hoped to survive but did not expect to. Western sources often incorrectly considerOperation Ten-Go as a kamikaze operation, since it occurred at the Battle of Okinawa along with the mass waves of kamikaze planes; however, banzai is the more accurate term, since the aim of the mission was for battleship Yamato to beach herself and provide support to the island defenders, as opposed to ramming and detonating among enemy naval forces. The tradition ofdeath instead of defeat, capture, and perceived shame was deeply entrenched in Japanese military culture. It was one of the primary traditions in the samurailife and the Bushido code: loyalty and honor until death; or in the Western vernacular “death before dishonor!”

Ensign Kiyoshi Ogawa, who dove his aircraft into theUSS Bunker Hillduring aKamikaze mission on May 11, 1945.

Naval battle

USS Bunker Hill burns after being hit by two kamikaze within 30 seconds

The British Pacific Fleet was assigned the task of neutralizing the Japanese airfields in the Sakishima Islands, which it did successfully from March 26 until April 10. On April 10, its attention was shifted to airfields on northern Formosa. The force withdrew to San Pedro Bay on April 23. On May 1, the British Pacific Fleet returned to action, subduing the airfields as before, this time with naval bombardment as well as aircraft. Several kamikaze attacks caused significant damage, but since the British used armored flight decks on their aircraft carriers, they only experienced a brief interruption to their force’s objective.

The bombardment from the sea at Okinawa

There was a hypnotic fascination to the sight so alien to our Western philosophy. We watched each plunging kamikaze with the detached horror of one witnessing a terrible spectacle rather than as the intended victim. We forgot self for the moment as we groped hopelessly for the thought of that other man up there.

Between April 6 and June 22, the Japanese flew 1,465 kamikaze aircraft in large scale attacks from Kyushu, 185 individual kamikaze sorties from Kyushu, and 250 individual kamikaze sorties from Formosa. When U.S. intelligence estimated 89 planes on Formosa, the Japanese had approximately 700 dismantled or well camouflaged and dispersed into scattered villages and towns; the U.S. Fifth Air Forcedisputed Navy claims of kamikaze coming from Formosa.

The ships lost were smaller vessels, particularly the destroyers of the radar pickets, as well as destroyer escorts and landing ships. While no major Allied warship was lost, several fleet carriers were severely damaged. Land-based motorboats were also used in the Japanese suicide attacks.

The protracted length of the campaign under stressful conditions forced Admiral Chester W. Nimitz to take the unprecedented step of relieving the principal naval commanders to rest and recuperate. Following the practice of changing the fleet designation with the change of commanders, U.S. naval forces began the campaign as the U.S. Fifth Fleet under Admiral Raymond Spruance, but ended it as the U.S. Third Fleet under Admiral William Halsey.

Operation Ten-Go

The Japanese battleship Yamatoexplodes after persistent attacks from U.S. aircraft

Operation Ten-Go (Ten-gō sakusen) was the attempted attack by a strike force of Japanese surface vessels led by the battleship Yamato, commanded by Admiral Seiichi Itō. This small task force had been ordered to fight through enemy naval forces, then beach themselves and fight from shore using their guns as coastal artillery and crewmen as naval infantry.

Tanks leaving the beach

The Yamato and other vessels in Operation Ten-Go were spotted by submarines shortly after leaving Japanese home waters, and were attacked by U.S. carrier aircraft.

Under attack from more than 300 aircraft over a two-hour span, the world’s largest battleship sank on April 7, 1945, long before she could reach Okinawa. U.S. torpedo bombers were instructed to only aim for one side to prevent effective counter flooding by the battleship’s crew, and hitting preferably the bow or stern, where armor was believed to be the thinnest.

The landing zone from above

Of the Yamato’sscreening force, the light cruiser Yahagi, and four out of the eight destroyers were also sunk. In all, the Imperial Japanese Navy lost some 3,700 sailors, including Itō, at the relatively low cost of just 10 U.S. aircraft and 12 airmen.

Land battle

The land battle took place over about 81 days beginning April 1, 1945.

The first Americans ashore were soldiers of the 77th Infantry Division, who landed in the Kerama Islands (Kerama Retto), 15 miles (24 km) west of Okinawa on March 26, 1945. Subsidiary landings followed, and the Kerama group was secured over the next five days. In these preliminary operations, the 77th Infantry Division suffered 27 dead and 81 wounded, while Japanese dead and captured numbered over 650. The operation provided a protected anchorage for the fleet and eliminated the threat from suicide boats.

Advancing carefully

On March 31 Marines of the Fleet Marine Force Amphibious Reconnaissance Battalion landed without opposition on Keise Shima, four islets just 8 miles (13 km) west of the Okinawan capital ofNaha. 155 mm Long Toms went ashore on the islets to cover operations on Okinawa.

Northern Okinawa

The battleship USS Idaho (BB-42) shellsOkinawa on 1 April 1945.

U.S. Marine reinforcements wade ashore to support the beachhead on Okinawa, March 31, 1945

The main landing was made by XXIV Corps and III Amphibious Corpson the Hagushi beaches on the western coast of Okinawa on L-Day, April 1, which was both Easter Sunday and April Fools’ Day in 1945. The 2nd Marine Division conducted a demonstration off the Minatoga beaches on the southeastern coast to confuse the Japanese about American intentions and delay movement of reserves from there.

US soldiers blast a Japanese held cave.

Tenth Army swept across the south-central part of the island with relative ease by World War II standards, capturing the Kadena and the Yomitan airbases. In light of the weak opposition, General Buckner decided to proceed immediately with Phase II of his plan—the seizure of northern Okinawa. The 6th Marine Division headed up the Ishikawa Isthmus. The land was mountainous and wooded, with the Japanese defenses concentrated on Yae-Take, a twisted mass of rocky ridges and ravines on theMotobu Peninsula. There was heavy fighting before the Marines finally cleared the peninsula on April 18.

Men and a Sherman tank of the 382nd Infantry Regiment, US 96th Division on the Ginowan Road, Okinawa, Japan, Apr-Jun 1945

Meanwhile, the 77th Infantry Division assaulted Ie Shima, a small island off the western end of the peninsula, on April 16. In addition to conventional hazards, the 77th Infantry Division encountered kamikaze attacks, and even Japanese women armed with spears. There was heavy fighting before Ie Shima was declared secured on April 21 and became another air base for operations against Japan.

Southern Okinawa

|

F4U Corsair fighter firingrockets in support of the troops on Okinawa

While the Marine 6th division cleared northern Okinawa, the U.S. Army 96th Infantry division and U.S. Marine 7th division wheeled south across the narrow waist of Okinawa. The 96th division began to encounter fierce resistance in west-central Okinawa from Japanese troops holding fortified positions east of Highway No. 1 and about about five miles (8 km) northwest of Shuri, from what came to be known asCactus Ridge. The 7th division encountered similarly fierce Japanese opposition from a rocky pinnacle located about 1,000 yards southwest of Arakachi (later dubbed “The Pinnacle“).

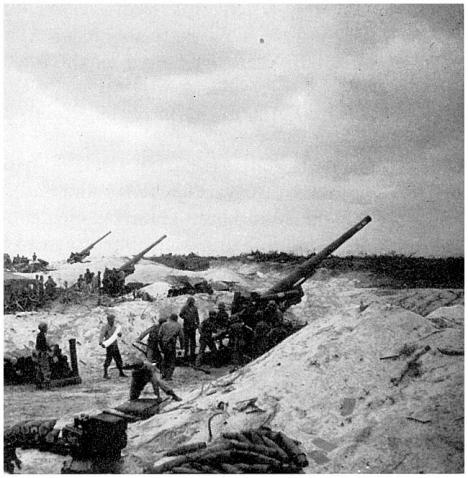

US guns boom. 155mm Gun set up on Keise Shima near Okinawa, Japan, Apr 1945

By the night of April 8 U.S. troops had cleared these and several other strongly fortified positions. They suffered over 1,500 battle casualties in the process, while killing or capturing about 4,500 Japanese, yet the battle had only just begun, for it was now realized they were merely outposts guarding the Shuri Line.

The next American objective was Kakazu Ridge, two hills with a connecting saddle that formed part of Shuri’s outer defenses. The Japanese had prepared their positions well and fought tenaciously. Fighting was fierce, as the Japanese soldiers hid in fortified caves, and the U.S. forces often lost many men before clearing the Japanese out from each cave or other hiding place. The Japanese would send the Okinawans at gunpoint out to acquire water and supplies for them, which induced casualties among civilians. The American advance was inexorable but resulted in massive casualties sustained by both sides.

Marines pass through a destroyed small village where a Japanese soldier lies dead, April 1945

As the American assault against Kakazu Ridge stalled, General Ushijima, influenced by General Chō, decided to take the offensive. On the evening of April 12, the 32nd Army attacked U.S. positions across the entire front. The Japanese attack was heavy, sustained, and well organized. After fierce close combat the attackers retreated, only to repeat their offensive the following night. A final assault on April 14 was again repulsed. The entire effort led 32nd Army’s staff to conclude that the Americans were vulnerable to night infiltration tactics, but that their superior firepower made any offensive Japanese troop concentrations extremely dangerous, and they reverted to their defensive strategy.

The 27th Infantry Division, which had landed on April 9, took over on the right, along the west coast of Okinawa. General Hodge now had three divisions in the line, with the 96th in the middle, and the 7th on the east, with each division holding a front of only about 1.5 miles (2.4 km).

Hodge launched a new offensive of April 19 with a barrage of 324 guns, the largest ever in thePacific Ocean Theater. Battleships, cruisers, and destroyers joined the bombardment, which was followed by 650 Navy and Marine planes attacking the enemy positions with napalm, rockets, bombs, and machine guns. The Japanese defenses were sited on reverse slopes, where the defenders waited out the artillery barrage and aerial attack in relative safety, emerging from the caves to rain mortar rounds and grenades upon the Americans advancing up the forward slope.

A 6th Division Marine demolition crew watches explosive charges detonate and destroy a Japanese cave, May 1945

A tank assault to achieve breakthrough by outflanking Kakazu Ridge, failed to link up with its infantry support attempting to cross the ridge and failed with the loss of 22 tanks. Although flame tanks cleared many cave defenses, there was no breakthrough, and the XXIV Corps lost 720 menKIA, WIA and MIA. The losses might have been greater, except for the fact that the Japanese had practically all of their infantry reserves tied up farther south, held there by another feint off the Minatoga beaches by the 2nd Marine Division that coincided with the attack.

Okinawan sculptor Kinjo Minoru’s relief depicting the horror of the Battle…

At the end of April, after the Army forces had pushed through the Machinato defensive line and airfield, the 1st Marine Division relieved the 27th Infantry Division, and the 77th Infantry Division relieved the 7th. When the 6th Marine Division arrived, III Amphibious Corps took over the right flank and Tenth Army assumed control of the battle.

On May 4, the 32nd Army launched another counteroffensive. This time Ushijima attempted to make amphibious assaults on the coasts behind American lines. To support his offensive, the Japanese artillery moved into the open. By doing so they were able to fire 13,000 rounds in support but an effective U.S. counter-battery fire destroyed dozens of Japanese artillery pieces. The attack was a complete failure.

American soldiers of the 77th Divisionlisten impassively to radio reports of Victory in Europe Day on May 8, 1945

Buckner launched another American attack on May 11. Ten days of fierce fighting followed. On May 13, troops of the 96th Infantry Division and 763d Tank Battalion captured Conical Hill. Rising 476 feet (145 m) above the Yonabaru coastal plain, this feature was the eastern anchor of the main Japanese defenses and was defended by about 1,000 Japanese. Meanwhile, on the opposite coast, the 6th Marine Division fought for “Sugar Loaf Hill”. The capture of these two key positions exposed the Japanese around Shuri on both sides. Buckner hoped to envelop Shuri and trap the main Japanese defending force.

By the end of May, monsoon rains which turned contested hills and roads into a morass exacerbated both the tactical and medical situations. The ground advance began to resemble aWorld War Ibattlefield as troops became mired in mud and flooded roads greatly inhibited evacuation of wounded to the rear.

Troops lived on a field sodden by rain, part garbage dump and part graveyard. Unburied Japanese bodies decayed, sank in the mud, and became part of a noxious stew. Anyone sliding down the greasy slopes could easily find their pockets full of maggots at the end of the journey.

Lt. Col. Richard P. Ross, commander of 1st Battalion, 1st Marines braves sniper fire to place the division’s colors on a parapet of Shuri Castle on May 30. This flag was first raised overCape Gloucester and then Peleliu

On May 29, Major General Pedro del Valle, commanding the 1st Marine Division, ordered Company A, 1st Battalion, 5th Marines to capture Shuri Castle. Seizure of the castle represented both strategic and psychological blows for the Japanese and was a milestone in the campaign. Del Valle was awarded aDistinguished Service Medal for his leadership in the fight and the subsequent occupation and reorganization of Okinawa. Shuri Castle had been shelled for 3 days prior to this advance by theUSS Mississippi (BB-41).[13] Due to this, the 32nd Army withdrew to the south and thus the marines had an easy task of securing Shuri Castle. The castle, however, was outside the 1st Marine Division’s assigned zone and only frantic efforts by the commander and staff of the 77th Infantry Division prevented an American air strike and artillery bombardment which would have resulted in many casualties due to friendly fire.

The Japanese retreat, although harassed by artillery fires, was conducted with great skill at night and aided by the monsoon storms. The 32nd Army was able to move nearly 30,000 men into its last defense line on the Kiyan Peninsula, which ultimately led to the greatest slaughter on Okinawa in the latter stages of the battle, including the deaths of thousands of civilians.

In addition, there were 9,000 IJN troops supported by 1,100 militia holed up at the fortified area of the Okinawa Naval Base Force in the Oroku Peninsula. Later that day, the Americans launched an amphibious assault on the Oroku Peninsula in order to secure their western flank. After several days of bitter fighting, the Japanese were pushed to the far south of the island.

On June 18, General Buckner was killed by enemy artillery fire while monitoring the progress of his troops. Buckner was replaced by Roy Geiger. Upon assuming command, Geiger became the only U.S. Marine to command a numbered army of the U.S. Army in combat. He was relieved five days later by Joseph Stilwell.

The island fell on June 21, 1945, although some Japanese continued hiding, including the future governor of Okinawa Prefecture, Masahide Ota.Ushijima and Chō committed suicide by seppuku in their command headquarters on Hill 89 in the closing hours of the battle. Colonel Yahara had asked Ushijima for permission to commit suicide, but the general refused his request, saying:

“If you die there will be no one left who knows the truth about the battle of Okinawa. Bear the temporary shame but endure it. This is an order from your army Commander.

Yahara was the most senior officer to have survived the battle on the island, and he later authored a book titled The Battle for Okinawa.

Casualties

Military losses

The last picture of Lieutenant GeneralSimon Bolivar Buckner, Jr., right, the day before he was killed by Japanese artillery on June 19, 1945

U.S. losses were over 62,000 casualties of whom over 12,000 were killed or missing. This made the battle the bloodiest that U.S. forces experienced in the Pacific war. Several thousand servicemen who died indirectly (from wounds and other causes) at a later date are not included in the total. One of the most famous U.S. casualties was the war correspondent Ernie Pyle, who was killed by Japanese machine gun fire on Ie Shima.U.S. forces suffered their highest-ever casualty rate for combat stress reaction during the entire war, at 48%, with some 14,000 soldiers retired due to nervous breakdown.

General Buckner’s decision to attack the Japanese defenses head-on, although extremely costly in U.S. lives, was ultimately successful. Just four days from the closing of the campaign, General Buckner was killed by Japanese artillery fire, which blew lethal slivers of coral into his body, while inspecting his troops at the front line. He was the highest-ranking U.S. officer to be killed by enemy fire during the war. The day after, a second general, Brigadier General Claudius M. Easley, was killed by machine gun fire.

![The Battle for Okinawa [Light]](https://i0.wp.com/library.thinkquest.org/19981/images/messages/7-2.jpg)

Aircraft losses over the three-month period were 768 United States planes including those bombing the Kyushu airfields launching kamikazes. Combat losses were 458, and the other 310 were operational accidents. Japanese aircraft losses were 7,830 over the same period, including 2,655 to operational accidents. Navy and Marine Corps fighters downed 3,047, while shipboard antiaircraft felled 409, and B-29s destroyed 558 on the ground.

At sea 368 Allied ships (including 120 amphibious craft) were damaged while another 28, including 15 amphibious ships and 12 destroyers were sunk during the Okinawa campaign. The U.S. Navy’s dead exceeded its wounded with 4,907 killed and 4,874 wounded, primarily from kamikaze attacks.Among United States casualties, neither the Army nor the Marine death toll exceeded the Navy death toll in the battle for Okinawa. The Japanese lost 16 ships sunk, including the giant battleship Yamato.

On land the U.S. forces lost at least 225 tanks and many LVTsdestroyed while eliminating 27 Japanese tanks and 743 artillery pieces (including mortars, anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns), some of them knocked-out by the naval and air bombardments but most of them knocked-out by American counter-battery fire. Casualties of American ground artillery are unknown.

A group of Japanese prisoners who preferred surrender to suicide wait to be questioned

By one count, there were about 107,000 Japanese combatants killed and 7,400 captured. Some of the soldiers committed seppuku or simply blew themselves up with hand grenades. In addition, thousands were sealed in their caves alive by the U.S. combat engineers.

This was also the first battle in the war in which surrendering Japanese were made into POWs by the thousands. Many of the Japanese prisoners were native Okinawans who had been impressed into the Army shortly before the battle and were less imbued with the Japanese Army’s no-surrender doctrine.

When the American forces occupied the island, the Japanese took Okinawan clothing to avoid capture and the Okinawans came to the Americans’ aid by offering a simple way to detect Japanese in hiding. The Okinawan language differs greatly from the Japanese language; with Americans at their sides, Okinawans would give directions to people in the local language, and those who did not understand were considered Japanese in hiding who were then captured.

Civilian losses

Okinawan civilians in 1945

Two Marines share a foxholewith an Okinawan war orphan in April 1945

At some battles, such as at Battle of Iwo Jima, there had been no civilians involved, but Okinawa had a large indigenous civilian population and, according to various estimates, somewhere between 1/10 and 1/3 of them died during the battle. Okinawan civilian losses in the campaign were estimated to be between 42,000 and 150,000 dead (more than 100,000 according to Okinawa Prefecture). The U.S. Army figures for the campaign showed a total figure of 142,058 civilian casualties, including those who were pressed into service by the Japanese Imperial Army.

During the battle, U.S. soldiers found it difficult to distinguish civilians from soldiers. It became routine for U.S. soldiers to shoot at Okinawan houses, as one infantryman wrote, “There was some return fire from a few of the houses, but the others were probably occupied by civilians – and we didn’t care. It was a terrible thing not to distinguish between the enemy and women and children. Americans always had great compassion, especially for children. Now we fired indiscriminately.

In its history of the war, the Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum presents Okinawa as being caught in the fighting between America and Japan. During the 1945 battle, the Japanese Army showed indifference to Okinawa’s defense and safety, and the Japanese soldiers used civilians as human shieldsagainst the Americans. Japanese military confiscated food from the Okinawans and executed those who hid it, leading to a mass starvation among the population, and forced civilians out of their shelters. Japanese soldiers also killed about 1,000 Okinawans who spoke in a different local dialect in order to suppress spying. The museum writes that “some were blown apart by shells, some finding themselves in a hopeless situation were driven to suicide, some died of starvation, some succumbed to malaria, while others fell victim to the retreating Japanese troops.

Mass suicides

With the impending victory of American troops, civilians often committed mass suicide, urged on by the Japanese soldiers who told locals that victorious American soldiers would go on a rampage of killing andraping. Ryukyu Shimpo, one of the two major Okinawan newspapers, wrote in 2007: “There are many Okinawans who have testified that the Japanese Army directed them to commit suicide. There are also people who have testified that they were handed grenades by Japanese soldiers” to blow themselves up.

Some of the civilians, having been induced by Japanese propaganda to believe that U.S. soldiers werebarbarians who committed horrible atrocities, killed their families and themselves to avoid capture. Some of them threw themselves and their family members from the cliffs where the Peace Museum now resides.

However, despite being told by the Japanese military that they would suffer rape, torture and murder at the hands of the Americans, Okinawans “were often surprised at the comparatively humane treatment they received from the American enemy. According toIslands of Discontent: Okinawan Responses to Japanese and American Powerby Mark Selden, the Americans “did not pursue a policy of torture, rape, and murder of civilians as Japanese military officials had warned.” Military Intelligence combat translator Teruto Tsubota, a U.S. Marine born in Hawaii, convinced hundreds of civilians not to kill themselves and thus saved their lives.

Rape allegations

Civilians and historians report that soldiers on both sides had raped Okinawan civilians during the battle. Rape by Japanese troops “became common” in June, after it became clear that the Japanese Army had been defeated One Okinawan historian has estimated there were more than 10,000 rapes of Okinawan women by American troops during the three month campaign. The New York Times reported in 2000 that in the village of Katsuyama, civilians formed a vigilante group to ambush and kill a group of black American soldiers whom they claimed frequently raped the local girls there.

Marine Corps officials in Okinawa and Washington have stated that they “knew of no rapes by American servicemen in Okinawa at the end of the war, and their records do not list war crimes committed by Marines in OkinawaHistorian George Feifer, however, writes that rape in Okinawa was “another dirty secret of the campaign” in which “American military chronicles ignore [the] crimes.” Few Okinawans revealed their pregnancies, as “stress and bad diet … rendered most Okinawan women infertile. Many who did become pregnant managed to abort before their husbands and fathers returned. A smaller number of newborn infants fathered by Americans were suffocated.

Suicide order controversy

Overcoming the civilian resistance on Okinawa was aided by U.S. propagandaleaflets, one of which is being read by a prisoner awaiting transport

There is ongoing major disagreement between Okinawa’s local government and Japan’s national government over the role of the Japanese military in civilian mass suicides during the battle. In March 2007, the national Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) advised textbook publishers to reword descriptions that the embattled Imperial Japanese Army forced civilians to kill themselves in the war so they would not be taken prisoner by the U.S. military. MEXT preferred descriptions that just say that civilians received hand grenades from the Japanese military.

This move sparked widespread protests among the Okinawans. In June 2007, the Okinawa Prefectoral Assembly adopted a resolution stating, “We strongly call on the (national) government to retract the instruction and to immediately restore the description in the textbooks so the truth of the Battle of Okinawa will be handed down correctly and a tragic war will never happen again.

On September 29, 2007, about 110,000 people held the biggest political rally in the history of Okinawa to demand that MEXT retract its order to textbook publishers on revising the account of the civilian suicides. The resolution stated: “It is an undeniable fact that the ‘multiple suicides’ would not have occurred without the involvement of the Japanese military and any deletion of or revision to (the descriptions) is a denial and distortion of the many testimonies by those people who survived the incidents.”

On December 26, 2007, MEXT partially admitted the role of the Japanese military in civilian mass suicides. The ministry’s Textbook Authorization Council allowed the publishers to reinstate the reference that civilians “were forced into mass suicides by the Japanese military,” on condition it is placed in sufficient context. The council report stated: “It can be said that from the viewpoint of the Okinawa residents, they were forced into the mass suicides. That was, however, not enough for the survivors who said it is important for children today to know what really happened.

The Nobel Prize winning author Kenzaburō Ōe has written a booklet which states that the mass suicide order was given by the military during the battle. He was sued by the revisionists, including a wartime commander during the battle, who disputed this and wanted to stop publication of the booklet. At a court hearing on November 9, 2007, Ōe testified: “Mass suicides were forced on Okinawa islanders under Japan’s hierarchical social structure that ran through the state of Japan, the Japanese armed forces and local garrisons.” On March 28, 2008, the Osaka Prefecture Court ruled in favor of Ōe stating, “It can be said the military was deeply involved in the mass suicides.” The court recognized the military’s involvement in the mass suicides and murder–suicides, citing the testimony about the distribution of grenades for suicide by soldiers and the fact that mass suicides were not recorded on islands where the military was not stationed.

Aftermath

American Sherman tanks knocked out by Japanese artillery Bloody Ridge April 20, 1945

Ninety percent of the buildings on the island were completely destroyed, and the lush tropical landscape was turned into “a vast field of mud, lead, decay and maggots”.

The military value of Okinawa “exceeded all hope.” Okinawa provided a fleet anchorage, troop staging areas, and airfields in close proximity to Japan. After the battle, the U.S. cleared the surrounding waters of mines in Operation Zebra, occupied Okinawa, and set up the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands, a form of military government.[47] Significant U.S. forces remain garrisoned there, and Kadena remains the largest U.S. air base in Asia.

Some military historians believe that the Okinawa campaign led directly to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as a means of avoiding the planned ground invasion of the Japanese mainland. Victor Davis Hanson explains his view in Ripples of Battle:

…because the Japanese on Okinawa… were so fierce in their defense (even when cut off, and without supplies), and because casualties were so appalling, many American strategists looked for an alternative means to subdue mainland Japan, other than a direct invasion. This means presented itself, with the advent of atomic bombs, which worked admirably in convincing the Japanese to sue for peace [unconditionally], without American casualties. Ironically, the American conventional fire-bombing of major Japanese cities (which had been going on for months before Okinawa) was far more effective at killing civilians than the atomic bombs and, had the Americans simply continued, or expanded this, the Japanese would likely have surrendered anyway.

Cornerstone of Peace Memorial with names of all military and civilians from all countries who died in the Battle of Okinawa

In 1945, Winston Churchill called the battle “among the most intense and famous in military history.”

In 1995, the Okinawa government erected a memorial named Cornerstone of Peace in Mabuni, the site of the last fighting in southeastern Okinawa. The memorial lists all the known names of those who died in the battle, civilian and military, Japanese and foreign. As of June 2008 it contains 240,734 names.

USS BUNKER HILL AT SEA

USS BUNKER HILL HIT BY KAMIKAZE

USS BUNKER HILL BURNING

USS BUNKER HILL DECK

USS FRANKLIN AFTER JAPANESE AIR ATTACK

KAMIKAZE ABOUT TO HIT USS MISSOURI

USS PRINCETON AFTER JAPANESE AIR ATTACK

KAMIKAZE ATTACK ON USS TICONDEROGA

![]()

USS TICONDEROGA DURING BETTER TIMES

LARGEST SHIP AFLOAT, YAMATO

YAMATO GOES DOWN

Leave a comment